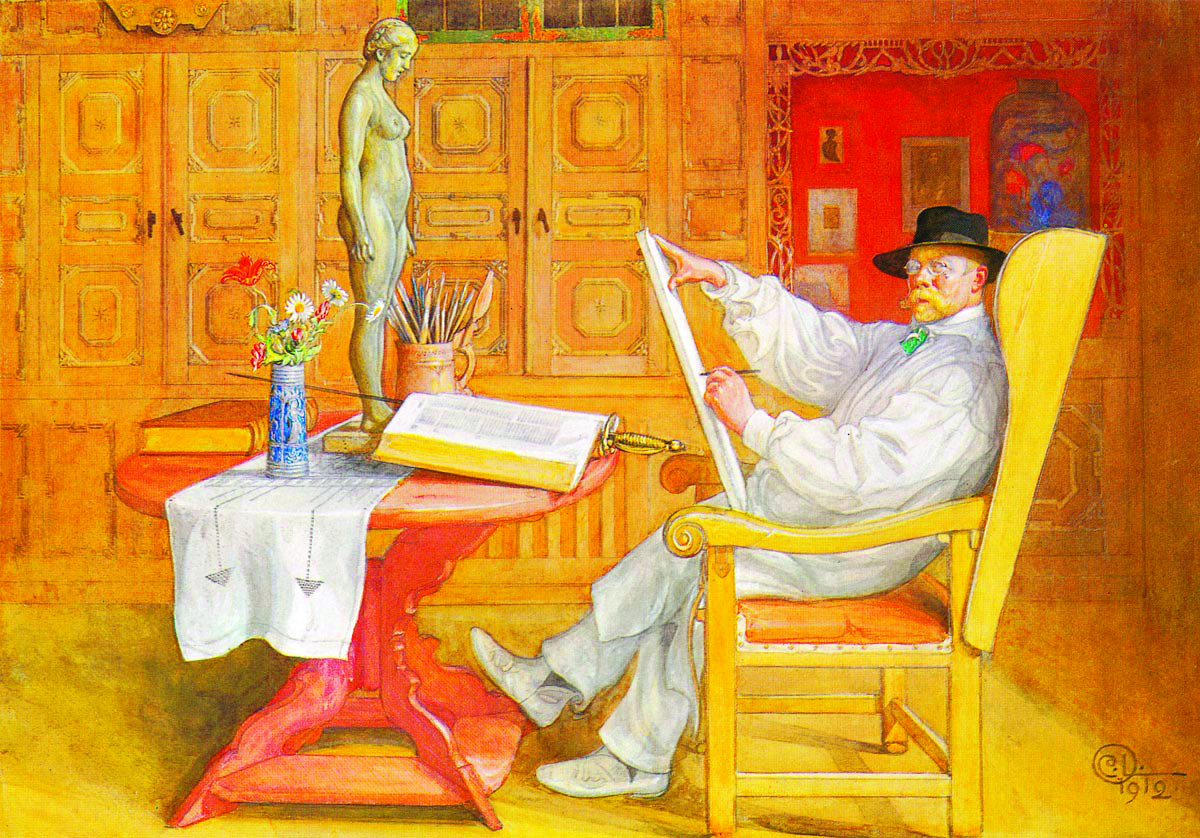

Carl Larsson – The Father of Swedish Design

No artist has made a more lasting impression on Swedish design than Carl Larsson. Paintings of his own family life and homestead in Dalarna became the archetype for the ideal Swedish home and an inspiration to future generations of designers. But who was he?

In his autobiography Jag, Carl Larsson tells the story of his life and art with a brutal honesty that was unusual for the times. While he finished his memoires a mere two days before his death in 1919, it would take twelve years until they were finally published in 1931, and still only in a censored version. In later, modern, editions the controversial parts have been reinserted, including portrayals of Carl’s miserable childhood, his hatred of his abusive father, and his sexual escapades before meeting his wife.

Larsson was born in 1853 in Stockholm where the family lived in abject poverty. One day, his father disappeared, and Carl’s mother was thrown out into the streets with her infant at her breast. A couple of “benevolent spinsters” gave her some food and advised her to become a laundress. A year later, Carl’s father returned, but his presence only added to the burden of the mother and her young child. Writes Carl: “An image indelibly engraved in my mind, a man with piercing eyes is sitting there crouched into the narrow space between the window and the dresser and says, maliciously: ‘Damned be the day when you were born.’ […] It must have been my robust grandmother who scared the igniter of my life spark to legally, in front of all the people, unite himself with the desperate woman who carried his child under her heart.”

The family lived in “one room and one kitchen, where big holes had been beaten into the walls, and these were full of cockroaches, armies of them, and other vermin. […] behold hell on earth! Starvation was the least of it. […] There were so many other difficult things. The feeble-minded of the city were boarded there, consumption ran rampant, there were bloody fights, prostitutes carried out their trade, murderers and thieves were pointed out.”

Hardly an auspicious beginning. Disease flourished and Carl’s brother John died young of tuberculosis.

At the age of thirteen, Carl’s teacher at the school for poor children encouraged him to apply to the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts where he eventually earned his first medal in nude drawing and was able to support himself as a caricaturist and graphic artist for newspapers. While at art school, Larsson also met and lost his first love. She died giving birth to their second child. The first child had already died.

Larsson, now a young man, left the surviving child with his mother and travelled to Paris where he received a letter informing him that the little girl was seriously ill and “’if the child did not die, it would live without using its mind fully.’ Never has anyone wrung his hands at the feet of God in a more urgent, passionate, crying manner. My prayers were heard! The young life expired,” Carl writes.

In Paris, Carl lived for the day. Poor and without any real artistic success, he avoided the French progressive impressionists but bonded with other Swedish artists. His autobiography depicts the decadent lifestyle of the artists who spent their last French sous on food and drink while indulging in local romances, feasts and orgies. However, the experience almost broke him. Destitute and too proud to ask for help, Carl stood on the banks of the river Seine contemplating drowning himself. He had just spent his two last coins on a fried pancake and decided to enjoy one last coffee and cognac on credit at Café de l’Erémitage before ending it all, when he happened to bump into a friend who came to the rescue.

Carl recovered at the Scandinavian artists’ colony Grez-sur-Loing outside Paris, where he met artist Karin Bergöö who would become his wife. In Grez, Larsson changed from oil painting to watercolor, the technique for which he would become most famous.

Carl and Karin Larsson raised seven children (the eighth died young) and the family became Carl’s favourite models.

In 1888, Karin’s father Adolf Bergöö gave them a small house named Little Hyttnäs at Sundborn, just outside Falun in Dalarna. Carl and Karin decorated and furnished this house which was then immortalized by Carl’s paintings of family life unfolding here. At first, the homestead served as their summer home, but in 1900 the family moved there permanently. A talented weaver, embroiderer, seamstress and interior designer, Karin created many of the interiors which Carl depicted.

As artists, they moved away from the dark and heavy style that was popular among the Swedish bourgeoisie of the 1800s, rejecting its stiff and artificial compositions of royalties and historic figures. They put simplicity above superficial and unnecessary extravagance. Theirs was a bright home that made room for child’s play – uncommon at the turn of the century. The paintings depict family life unfolding, with its chaos, wrinkled up carpets and half-dressed kids. Celebrating old traditions was important to the family, yet their lifestyle was very modern. The children ate at the same table as the adults, and they were allowed to play and roam about which surprised many guests who visited the family.

The Larssons wanted their idea of beauty to reach all layers of society, including the growing working class. Carl created illustrated books with watercolor paintings depicting their home and family life. His most famous book Ett hem (A Home), published in 1899, became very popular both in Sweden and abroad. It would forever shape how generations of Swedes visualized the ideal home. In it, Carl wrote: “Therefore, oh Swede, save yourself in time. Return to simplicity and dignity. It is better to be awkward than elegant. Dress yourself in skin, fur, leather, and wool. Make yourself furnishings that suit your heavy body, and on everything put bright colors.”

Little Hyttnäs became the embodiment of the notion of the Swedish folkhem (People’s Home) of the 20th century. The Larssons even designed their own furniture and designers from Ikea still make mandatory visits to the homestead every year for their annual dose of timeless Swedish design. As recently as 2018, Swedish clothing company H&M also turned to Carl Larsson-gården for inspiration for their Conscious Exclusive-collection.

Little Hyttnäs remains one of the most famous artist’s homes in the world. The descendants of Carl and Karin Larsson own the homestead, now known as Carl Larsson-gården, and it is open for visitors from May until October.

By Kajsa Norman