Lucia

The Lucia tradition can be traced back both to the martyr St Lucia of Syracuse (died in 304) and to the Swedish legend of Lucia as Adam’s first wife. It is said that she consorted with the Devil and that her children were invisible infernals. The name may be associated with both lux (light) and Lucifer (Satan), and its origins are difficult to determine. The present custom appears to be a blend of traditions.

In the old almanac, Lucia Night was the longest of the year. It was a dangerous night when supernatural beings were abroad and all animals could speak. By morning, the livestock needed extra feed. People, too, needed extra nourishment and were urged to eat seven or nine hearty breakfasts. The last person to rise that morning was nicknamed ‘Lusse the Louse’ and often given a playful beating round the legs with birch twigs. In agrarian Sweden, young people used to dress up as Lucia figures (lussegubbar) that night and wander from house to house singing songs and scrounging for food and schnapps.

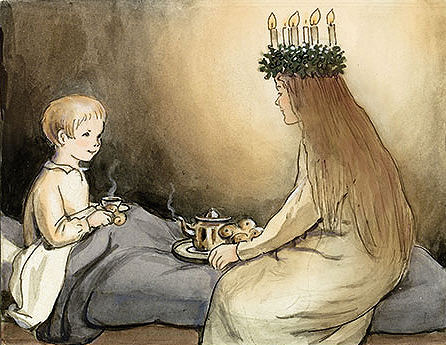

The first recorded appearance of a white-clad Lucia in Sweden was in a country house in 1764. The custom did not become universally popular in Swedish society until the 1900s, when schools and local associations in particular began promoting it. The old lussegubbar custom virtually disappeared with urban migration, and white-clad Lucias with their singing processions were considered a more acceptable, controlled form of celebration than the youthful carousals of the past. Stockholm proclaimed its first Lucia in 1927. The custom whereby Lucia serves coffee and buns (lussekatter) dates back to the 1880s.

Who gets to be Lucia?

There used to be a competition for the role of Lucia – on national TV as well as on a local level in towns and schools all over the country. Local newspapers invited subscribers to vote for one or other of the candidates. Today, no national ‘Lucia of Sweden’ is elected and schools often let chance decide who’s to be Lucia, for example by organising a draw.

In general, Sweden avoids ranking people, which is why beauty contests and ‘homecoming queen’ events are rare. The Lucia celebration used to be an exception, until it was deemed obsolete.

Lucia − the bearer of light

Alongside Midsummer, the Lucia celebrations represent one of the foremost cultural traditions in Sweden, with their clear reference to life in the peasant communities of old: darkness and light, cold and warmth.

Lucia is an ancient mythical figure with an abiding role as a bearer of light in the dark Swedish winters.

The many Lucia songs all have the same theme:

The night treads heavily

around yards and dwellings

In places unreached by sun,

the shadows brood

Into our dark house she comes,

bearing lighted candles,

Saint Lucia, Saint Lucia.

All Swedes know the standard Lucia song by heart, and everyone can sing it, in or out of tune. On the morning of Lucia Day, the radio plays some rather more expert renderings, by school choirs or the like. The Lucia celebrations also include ginger snaps and sweet, saffron-flavoured buns (lussekatter) shaped like curled-up cats and with raisin eyes. You eat them with Swedish mulled wine (glögg) or coffee.

Source: https://sweden.se

Po Tidholm is a freelance journalist and a critic based in the province of Hälsingland. In the collection ‘Celebrating the Swedish Way’, he has written the main sections about how we celebrate in Sweden today.

Agneta Lilja is a lecturer in ethnology at Södertörn University College, Stockholm. She also writes reviews and appears on radio and tv. In the collection ‘Celebrating the Swedish Way’, Lilja has written the sections about the history of Swedish traditions and festivities.

First published December 13, 2020