Fapur, Mopir, Sun, Dottær and the Law

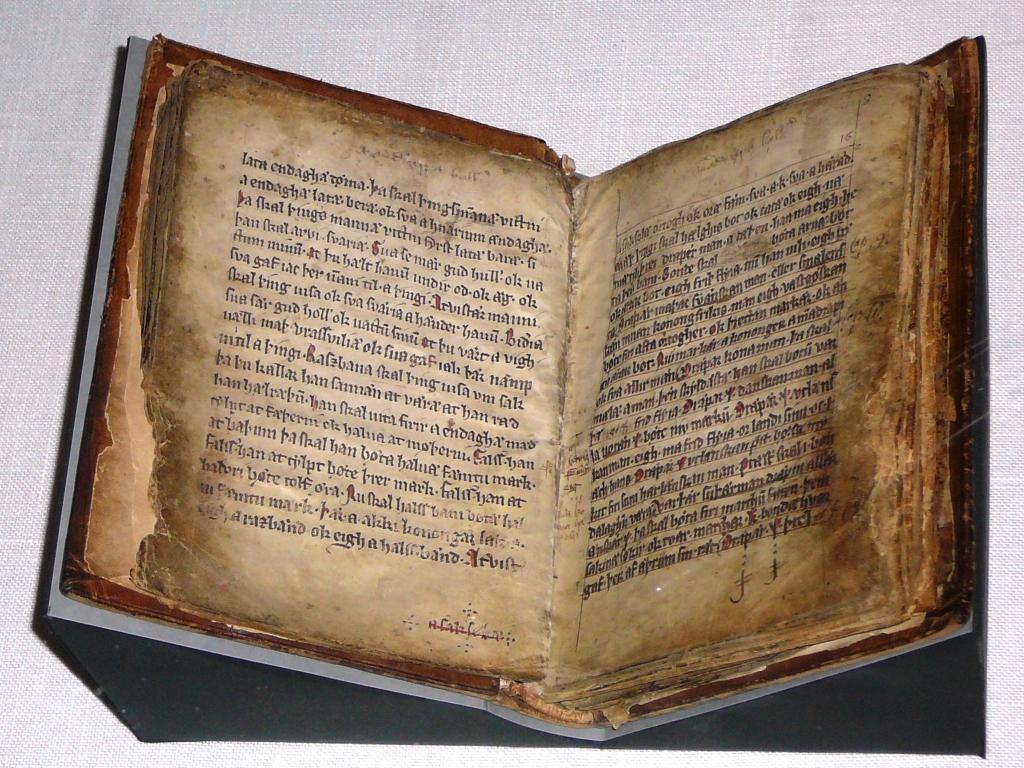

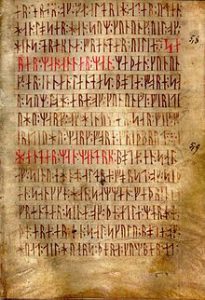

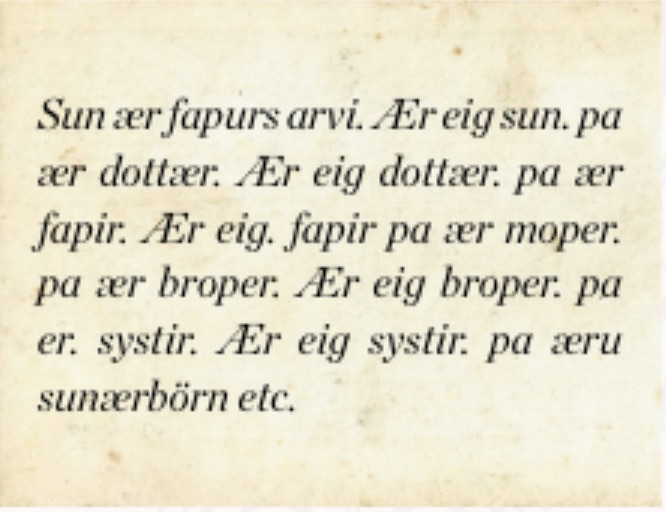

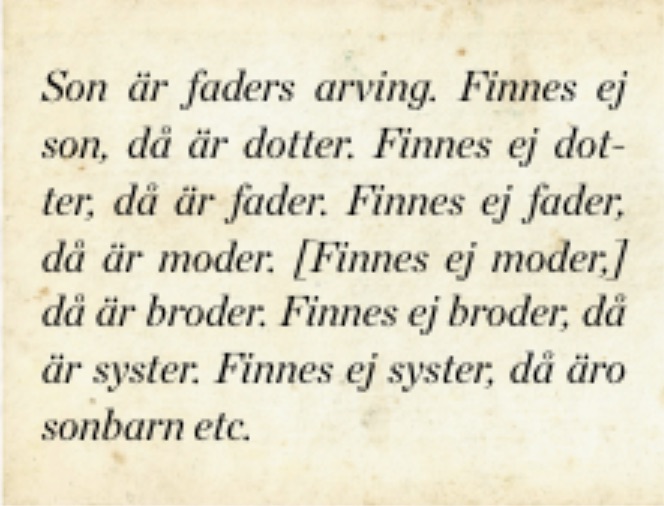

Before the 8th century, the peoples of Scandinavia spoke more or less the same Germanic language called Proto-Norse. During the Viking period it evolved into separate dialects known as Old West Norse and Old East Norse. The Old East Norse spoken in Sweden became known as Runic Swedish, because most of the written records from the period used runes – that angular alphabet that Vikings used to chisel into rune stones. The runes gave way to Latin letters when Christianity took hold in Sweden. The earliest written sample in Latin script is found in the Västgötalagen, a law book written in the 13th century. Here is a taster:

For a native Swedish-speaker it is not too difficult to follow how the language evolved. Most people can just about read 13th century Swedish by studying a page or two in the law book, keeping a modern translation on the side.

In the same century parts of Sweden joined the Hanseatic League, a forerunner of the European Union which was heavily dominated by the Germans. The Swedish language was enriched with Middle Low German vocabulary. (Example: Stadt in Ger-man became stad in Swedish.) After 1818 the language assimilated a large number of French words when one of Napoleon’s generals was head-hunted to became King of Sweden. (Example: fauteuil in French became fåtölj in Swedish.)

Fast forward to the mid-20th century when American English began to infiltrate the language, to the chagrin of Swedish linguistic purists who maintain that the English words have eclipsed perfectly adequate Swedish equivalents. (Example: vocabulary in English has become vokabulär in Swedish, when the Swedish word ordförråd does the same job.) Another English language influence is the habit of younger Swedes to split up written compound nouns and adjectives into their element parts which sometimes leads to hilarious misunderstandings. Dividing up “En brunhårig sjuk-sköterska” (verbatim: “A brownhaired sicksister”, i.e. a nurse) yields “En brun hårig sjuk sköterska”, which will be understood as “A brown hairy sick sister”.

According to +Babbel Magazine, Swedish is the second easiest foreign language for English-speakers to learn (the easiest of all is Norwegian). The reason is that many words are the same, and the grammar is not too different either. However, Swedish nouns do come in two genders which have to be learned by heart, similar to le and la in French. Another peculiarity is that the English “the” is tacked on at the end of nouns. (Example: “the car” in English becomes “bilen” in Swedish, and “the cars” becomes “bilarna”.)

Then there is Swedish pronunciation. In the 1950s Scandinavians were exempted from carrying passports when travelling between Sweden, Norway and Denmark … but not non-Scandinavians. At the ferry terminal in Malmö, incoming travellers from Copenhagen had to choose between two doorways, one marked “For Scandinavian Citizens” (i.e. no need to show a passport) and the other “For Non-Scandinavians” (passport required). To catch any Non-Scandics trying to sneak through without a passport, an immigration official was posted just beyond the “Scandinavian” doorway who challenged each traveller with the words “Say after me: sjutusen sjuhundra sjuttisju” (Swedish for “7777”). Only true Scandinavians pronounce this correctly. Arriving from Copenhagen, I once amused myself by affecting a foreign accent and failed the test. I was less amused after having to spend another 15 minutes in an interrogation room …

By learning Swedish, do you get Norwegian and Danish thrown in for free? Well, not quite. It is true that Norwegians and Danes can understand each other without difficulty, but Swedes are different. Understanding spoken Norwegian is manageable as long as the speaker doesn’t use one of the many dialects. Spoken Danish is another matter. I grew up in Malmö across the Strait of Öresund from Copenhagen, so I understand Danish better than many Swedes, but it can still be a struggle. One technique I have developed is that, after listening to a Danish-speaker for a few minutes, I developa kind of mental phonetic look-up table, and from then onwards I man-age to understand spoken Danish fairly well. I can do the same thing with Norwegian. But memorably, on one occasion I had dinner with Danish and Norwegian colleagues. Switching my concentration back and forth between the two languages threw my fragile look-up tables out the window. I hardly understood a word of what was said all evening.

by Peter Berlin