Evolution of Swedish Folk Music

In recent years Sweden has been recognized as one of the world’s most impressive pop-music contributors, with its musical artists and producers dominating the contemporary pop landscape at home and abroad. With so much attention given to Sweden’s stake in the future of music, it seems high time that we take a glance back at the origins of the country’s musical sensibilities. We hope to better understand what “music” in Sweden meant before the days of ABBA and Max Martin.

Early Swedish music was primarily constituted by ballads and kulning, or herding calls. Kulning is a song typically sung by women for the purpose of calling sheep and cows down from the hills upon which they graze. Evidence suggests that its use dates as far back as the domestication of animals in medieval times. Kulning’s vocalizations are marked by many quartertones and halftones – which are often referred to as “blue tones” – leading to a haunting, ghostly effect.

When not out in the hills, Swedes played melodies on instruments like the nyckelharpa and the fiddle. The nyckelharpa, or the “key fiddle,” is a traditional instrument that employs key-actuated tangents to change pitch. Traces of the instrument’s existence on a church relief in Gotland date the instrument to 1350. Though it was widespread in the 15th and 16th centuries, it wasn’t until the early 17th century that the nyckelharpa truly took hold, particularly in the province of Uppland.

Much like the nyckelharpa, but more streamlined in construction, the fiddle came to Sweden in the early 17th century and quickly became the instrument of choice for many musicians. It is arguably the paradigmatic instrument of Swedish folk music, enabling jaunty polska songs as well as leisurely “gånglåtar” or “walking tunes.” Folk musicians were known as “spelmän” (men who play) and were integral to dances and ceremonies in rural Swedish towns. Jämtland’s Lapp-Nils, Bingsjö’s Pekkos Per and Malung’s Lejsme-Per Larsson were all beloved, virtuoso fiddlers, though they were sadly never recorded.

Despite a wave of religious fundamentalism that reached Scandinavia in the 19th century and posited music as sinful, folk musicians continued to entertain their small towns through lilting melodies and dexterous playing. Still, the folk music tradition was diffuse and songs weren’t well documented. It wasn’t until the formation of Götiska Förbundet in 1811 that Sweden’s musical tradition was examined and treated formally as an essential part of the country’s cultural heritage.

Götiska Förbundet, or the Gothic Society, was formed shortly after Sweden’s 1809 transition to a modern constitutional monarchy. Nostalgic for a bygone era, a group of Scandinavian academics started the society to advance literary and poetic studies, with an eye towards contemplating Scandinavian antiquity. They saw the early Swedish agrarians as uncomplicated, untainted and originary and hoped to better understand them through analyses of their cultural output. Swedish folk music traditions, consequently, were studied and archived. Though the society was short-lived (it dissolved after a decade long dormancy in 1844), it managed to shine a light on the country’s musical traditions with Arvid Afzelius’s groundbreaking anthology of folksongs: “Swedish Songs from Antiquity.”

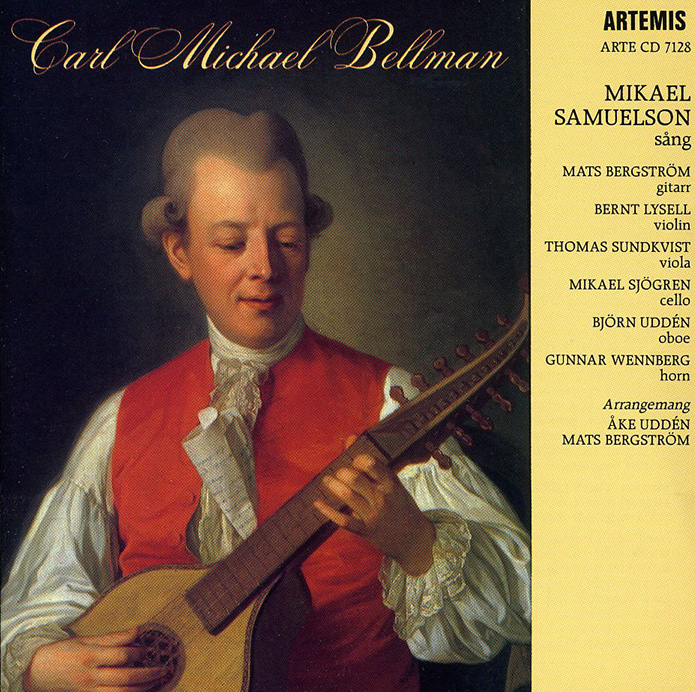

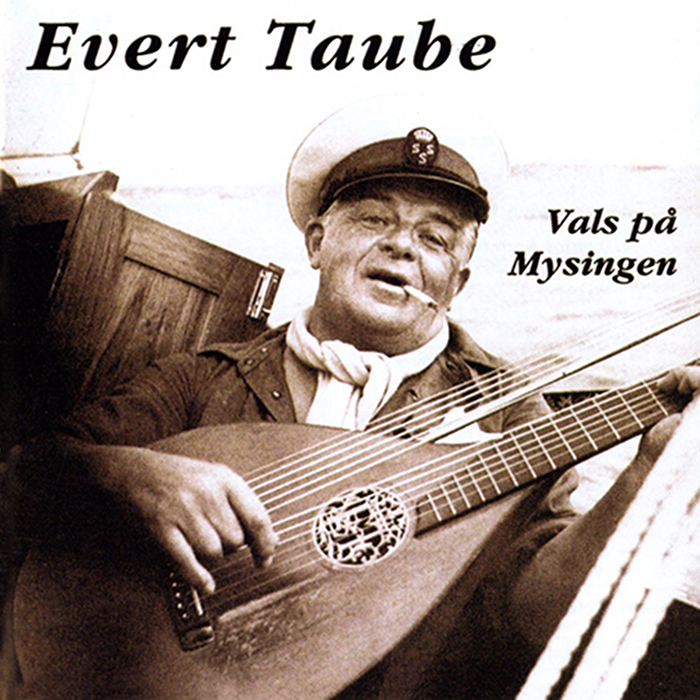

Included in Afzelius’s anthology of songs were some from Sweden’s extensive ballad tradition. Equally as much a part of Sweden’s musical heritage as instrumental folk music, Swedish ballads were known for their poetic, narrative quality. The genre originated at the end of the 18th century with Carl Michael Bellman, who delivered songs that ranged in tone from romantic to satirical, from humorous to elegiac. Swedish troubadours such as Bellman briefly fell out of fashion in the 19th century, but the 20th century welcomed one of Sweden’s most beloved troubadour musicians: Evert Taube. With his first performances in the 1920s, Taube sang tales of his time abroad in Argentina and at sea, often representing a yearning for the romantic landscape of the Swedish archipelago.

While the popularity of Taube’s ballads endured into the mid-20th century, interest in folk music waned and musicians began to meet in informal settings to learn from one another and develop their skills. Fiddling had theretofore been a solitary practice, but in the second half of the 20th century such informal music sessions led to the formation of amateur musical groups, or spelmänslag. These music groups were primarily located in Dalarna and typically considered outdated.

That all changed, however, when the youth of 1960s Sweden brought about a roots revival. Inspired by the wave of folk music spreading throughout the United States, many young Swedes took up the nyckelharpa, fiddle and accordion and created their own spelmänslag. They played on mainstream TV and radio channels, giving new life to a dying tradition.

The beginning of the 1970s ushered in a taste for jazz, rock and pop and the folk music tradition slowly faded from the foreground of the Swedish music scene. Now, we can find traces of both the ballad and the folk music tradition in all corners of the country. Musicians like Lars Winnerbäck are our contemporary troubadours, broadening the scope of ballad texts to include political musings and social critique; and in many cities there exist folk societies such as Folkmusikhuset in Stockholm, where guests are encouraged to fiddle and dance. With the summer season upon us, it is the perfect time to turn on some Taube and sink into a wave of Scandinavian nostalgia.

by Lara Anderson

First published August 1, 2016