Manitoba – Where Swedish Roots Run Deep

“This is it,” says Alvin Goranson and points to the rows of Swedish tombstones behind him at the Nord cemetery just west of Eriksdale, Manitoba. Cenotaphs and rocks are the only markers left on the land his parents and grandparents once came to Canada to farm.

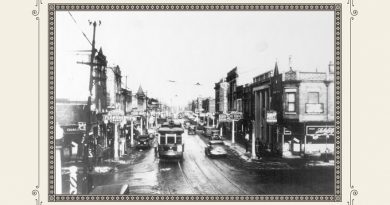

Immigration from Sweden to Canada started slowly. However, with the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) to Winnipeg in 1881 and British Columbia in 1885, the prairies opened up to homesteaders and Winnipeg became the Nordic gateway to the West. A rail and retail centre also known as the “Chicago of the North,” most Swedes passed through Winnipeg as part of the immigration process.

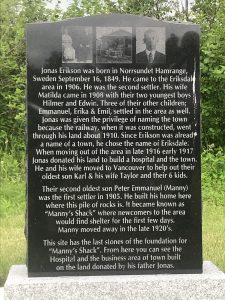

The Canadian government and the CPR did their best to attract Swedish immigrants to Canada through advertisement and agents in Sweden. In 1885, the government set aside two tracts of land for Scandinavian immigrants. One, located north of Whitewood in Saskatchewan, was known as New Stockholm. The other, located northwest of Winnipeg near Minnedosa, was known as “New Sweden” or Scandinavia. In 1908, the community of Avesta was established. Later, the name was changed to “Erickson”, in honour of the first Postmaster, a Swedish immigrant named Albert Erickson.

Of the Swedes who settled in Manitoba nearly half lived in or around Winnipeg, which remained the “Swedish capital of Canada” until the 1940s when Vancouver took over the title. The rest spread westward to places like Scandinavia, Erickson, Hilltop and Smoland, eastward to the Lac du Bonnet/Riverland area, or, like Alvin Goranson’s parents, northward to Eriksdale/Lillesve in the Interlake region.

“If there was nothing else to do, we were told to go pick rocks,” Alvin remembers. “There was never an idle moment.”

While he doesn’t farm anymore, Alvin and his wife have stayed in the area. So has his son Todd who now works for the Department of Agriculture. But while the pastoral landscape is reminiscent of Sweden, the legacy of the Swedes who once farmed these lands is vanishing.

When asked what remains of his Swedish heritage, Todd Goranson replies:

“We maintain some of what we would call traditional Swedish foods, mostly at Christmas. We make a Swedish thin bread and eat Lutfisk, but the language is gone,” he says.

86-year-old Alvin is the last family member still able to understand and speak Swedish.

As for Todd he only knows one phrase: “Ät och tig; shut up and eat!” he laughs.

By Noelle Norman