Andersonville, Chicago

History records September 18, 1838, as the date when Olof Gottfrid Lange became the first Swedish immigrant to settle in Chicago. He opened a drug store but didn’t stay long before heading north to become the first Swedish settler in Milwaukee.

About two years later, Swedish-born farmer John Anderson acquired several plots of land that he cultivated in the area known as Lakeview. He also served as highway commissioner from 1850 to 1857 and is thought to have coined the name Andersonville for his bailiwick.

Settlement in Andersonville was slow until Swedetown settlements in the south were wiped out in the Great Chicago Fire of October 1871. People were thereafter prohibited by city ordinance from building new homes of wood. No such prohibition existed in Andersonville, which was outside city limits.

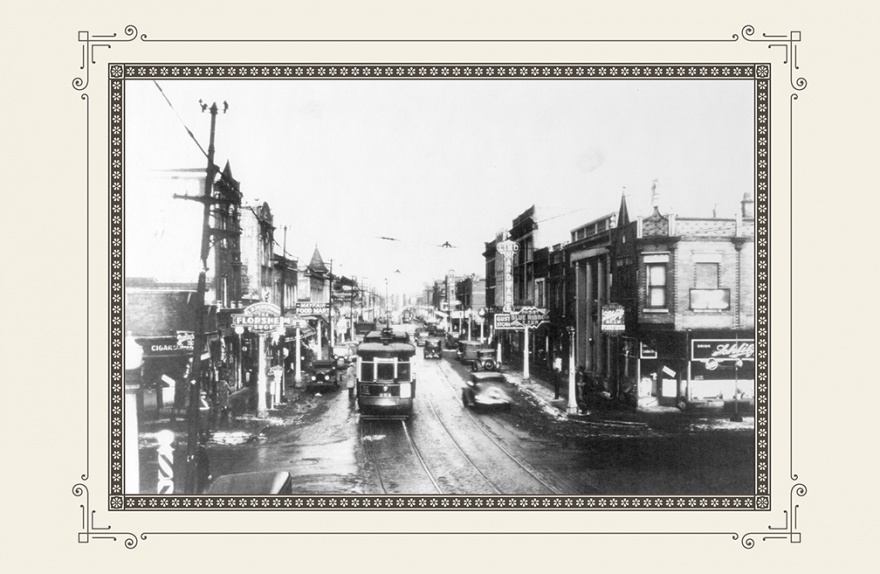

A period of rapid growth of the Swedish community followed with such additions as Ebenezer Lutheran Church in 1892, Lyman Trumbull School in 1908 and several businesses around Clark and Foster (originally Green Bay Road and 59th Street).

Among the businesses that migrated to Andersonville was Lind & Severin Hardware. Founded in 1888 in a Swedetown on Oak Street, the store relocated to 5209 N. Clark in 1909. In 1927, Lind Hardware moved into a new three-story building at 5211 N. Clark designed by Swedish architect Andrew (Anders) Norman.

By 1900, an estimated 150,000 people of Swedish descent lived in Chicago neighborhoods like Ander-sonville, making this combined community the second largest after that of Stockholm, the capital city of Sweden. Growth continued until 1930, when the Great Depression paralyzed the United States. Lind Hardware survived, along with Ericksson’s Delicatessen, Schott’s Fishmarket (later Wikstrom’s), the Villa Sweden restaurant, and six bakeries.

Another survivor was Simon Lundberg’s street level café, founded in 1919. When Prohibition started in 1920, Swedes could still get spiked coffee in the basement N.N. Club (No Name), a speakeasy. Since the end of Prohibition in 1934, the landmark has been known as Simon’s Tavern.

Although Andersonville received a first prize for neighborhood participation during the 1933 Century of Progress – the Chicago World’s Fair – times were tough for residents and businesses.

A further impediment to renewal after World War II was the inability of returning servicemen to find city lots on which to use the G.I. Bill to build homes for their new families. The suburbs grew as major highways made them more accessible.

A renaissance began after two decades of blight that included the closing of Lind Hardware and many other Swedish family firms. On October 17, 1964, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley and Illinois Governor Otto Kerner attended the celebration for designation of Andersonville as an official city neighborhood.

A decade later, the establishment of a Swedish American Museum focused new public attention on the importance of Scandinavian immigration to the neighbourhood.

by Stephen Anderson